Selection Rules

What electronic transitions are allowed?

So far in our quantum courses, we’ve become familiar with the idea that certain rules or requirements must be considered when determining which transitions are allowed between different energy states. Selection rules have been introduced through the perspective of operators operating on a wavefunction. If the integral of the transision operator acting upon the wavefunction both before and after the transition is zero, then the transition will not occur. Orbital momentum must be conserved in the transition, and if the momentum of the photon is not conserved, then the transition will not occur. These are two explanations of selection rules that we heard in Chem 301, and we can better understand allowed transitions by thinking of these transitions as linear combinations of different energy states.

Conservation Rules

We can simplify the idea of conservation by translating it to the idea of symmetry. If the energy of a system is the same at two different times, we say that the energy of that system is then conserved. Conservation is a construct. We want energy to be conserved because we say it is constant. Time symmetry implies energy conservation. If the rotational symmetry is conserved, then angular momentum is also conserved. If the position symmetry is conserved - if the same thing can happen over a different space - linear momentum is conserved.

Back to Selection Rules

The mechanism which allows for the transition will define which transitions are allowed. We’ve been talking about electric dipole moments - where light is an oscillating electric field.

What are dipoles?

Permanent dipole moments are uninteresting in this context, as we are actually interested in oscillating dipole moments, but we must first think of the expression used to describe a dipole. This expression scales linearly with separation and charge:

${\mu = q * d}$

Where ${\mu}$ is the dipole moment, ${q}$ is the charge, and ${d}$ is the displacement.

If we have more than one charge/dipole, we will sum the dipole moments.

The oscillating dipole allows us to “take” the energy from the electromagnetic field to apply to some object. Remember that the sine wave model is used to show the propagation of an electromagnetic field. The amplitude is representative of the vectors which would represent what force a positive test charge would feel in the electromagnetic field. The sign indicates the direction and the length of the vector indicates the magnitude of the field. If the electromagnetic field interacts with the dipole and causes it to stretch and compress, then we say it is an oscillating dipole. If the orientation of the diole is such that the dipole is horizontal along the electric field, the electric field applies a torque that causes the dipole to rotate as it encounters the electromagnetic field.

What sort of wavelengths or energies work?

When the incoming frequency of the oscillating field matches the frequency of the natural oscillation of the distant dipole absorbance increases. At the resonance frequency, the efficiency with which you can couple the energy is maximized.

Now let’s apply these concepts to our quantum systems. Let’s use particle in a box because it is familiar. Imagine a proton outside of the box so that we have a dipole moment. Let’s put the electron in a familiar, stationary state. There is a dipole, a fixed (both the positive charge and the electron are time independent, so fixed), between the positive charge and the electron in the well. Remember the dipole only depends on charge and distance.

Because we are describing probability values, we probably want to use the expectation value for position to describe the distance between the positive charge and electron. When you have a linear combination of stationary states, you get an oscillating dipole moment because the expectation value of position is changing, and thus the distance between the electron and the fixed charge is changing - it is oscillating.

Now let’s apply this idea to atomic orbitals and think about what transitions would be allowed.

Can I go from a 1s to a 2px by absorbing a photon?

In the 1s and 2p_x, we don’t have an oscillating dipole moment because we expect the dipole moment to be zero. We expect the electron, on average, to be found at the nucleus, so the dipole moment between the two would be zero, distance equals zero. But throughout this transition, there is an oscillating dipole. Let’s describe the transition from 1s to 2px with a transition dipole moment, as a linear combination of the 1s and the 2px atomic orbitals. The probability of being in 1s vs being in 2px can vary over time, so we will have time varying coefficients to describe the contributions of 1s and 2p. The transition dipole moment results from the constructive and destructive interference of the 1s and 2p_x orbitals. With time, the phase of the 2p_x orbital is changing faster than the 1s atomic orbital changes phase, which gives rise to an oscillating dipole.

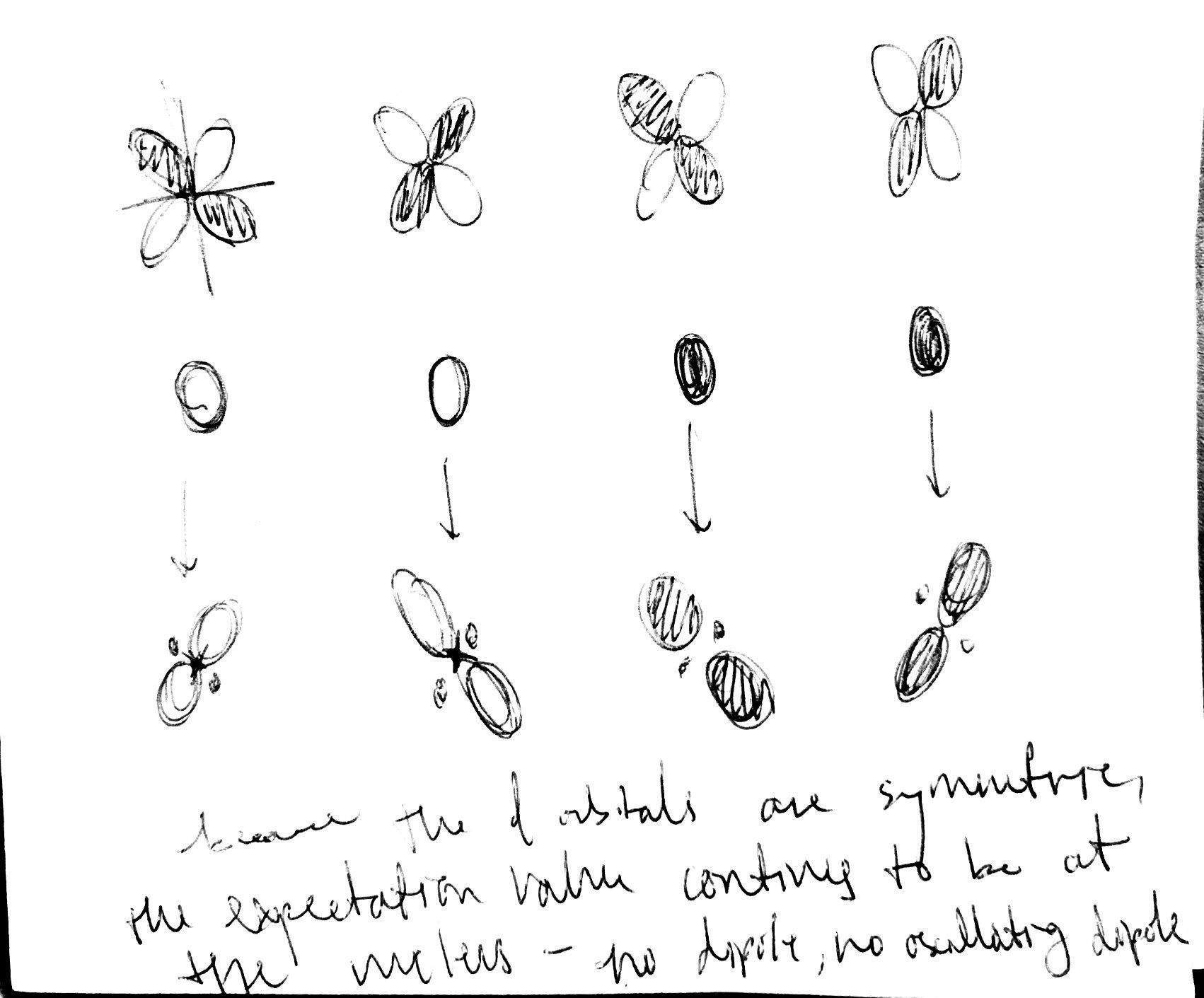

Transition from 1s to 3d - is it allowed?